Making VisuaLeague

Blog post by Haakon A. Ikonomou.

A central part of the INNER_LEAGUE project will be a giant prosopographical database and a publicly available digital research tool, expanding on my previous work on the digital prosopographical research tool VisuaLeague.1 As this is the case, I thought a first blog entry could be about the ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ of VisuaLeague – and about the many ideas we have for a new version.

What is VisuaLeague?

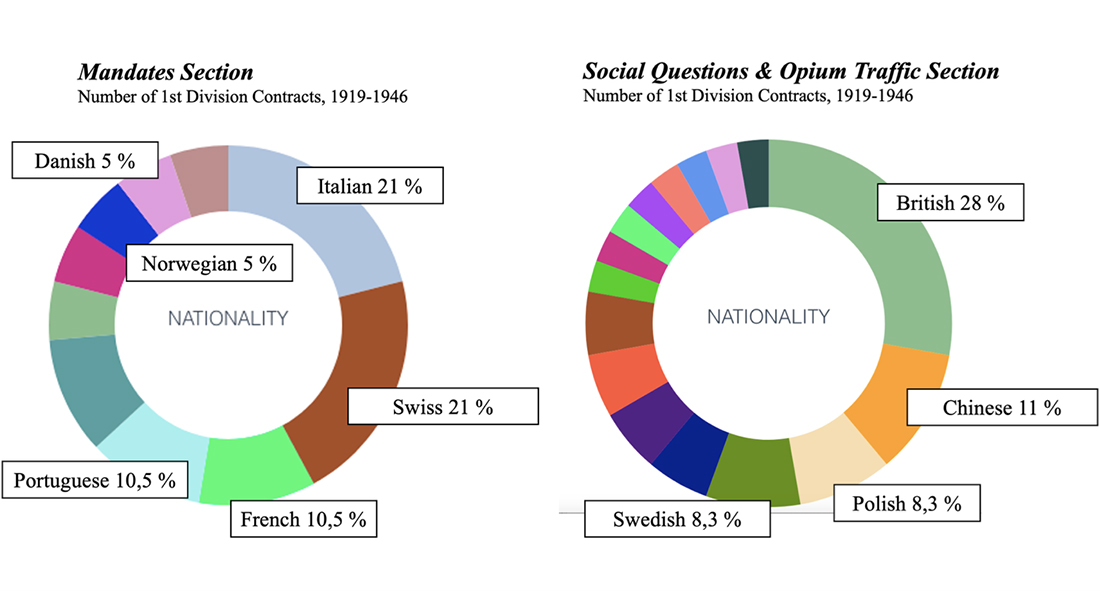

VisuaLeague is a digital prosopographical research tool, where scholars can select, combine and search on the nationality, gender, age, position and paygrade of all employees of the League Secretariat within any given time span of the League’s existence. This automatically generates basic statistical representations and visualisations of the group you have selected, and it creates a curated prosopographical dataset, that you can download as an excel sheet, as a first step towards your own research.

So, if – for instance – you want to know about the Swiss, French and Italian Messenger Cyclists, Drivers, Motorcyclists and Lift Attendants of the League Secretariat, between 1925 and 1936, you can chose those variables, and basic statistics about these people will be generated, along with a list of, in this case, 150 entries: contracts, names, positions, institutional affiliation, division (paygrade) and nationality.

How did we make VisuaLeague?

But how was this tool made? It took standing on the shoulders of previous archival and prosopographical work, some very well-timed developments elsewhere and hard work from a whole lot of people.

Let’s start with the first. The remarkable starting point for all of this is that the League of Nations’ archives (based at the United Nations Library and Archives in Geneva) contain the personnel files of all employees of the Secretariat. These have been available in the archives for a long time, a rarity for any organisational archive. And recently, with the Total Digital Access to the League of Nations Project (LONTAD), all the files were digitised and OCR-scanned.2

Long before the files were digitised, however, Professor Madeleine Herren and a large team of historians and students, based at Heidelberg University, manually coded all these personnel files, along with a number of other sources and handbooks, to create the LONSEA database. LONSEA was the first publicly available digital prosopographical and network-based research tool on international organisations, internationalists and global governance in the interwar period.3 We shall return to it.

In 2016, when I joined Karen Gram-Skjoldager’s project The Invention of International Bureaucracy4 (Aarhus University, IRFD) as a postdoc, we were granted access to the prosopographical database behind LONSEA – basically an excel sheet, which we could use for our own work. This was when I realised the potential of prosopography, working closely together with Karen Gram-Skjoldager, Torsten Kahlert and Emil Seidenfaden. A multitude of exciting research findings emerged from working with the dataset.5

Later, in 2021, I was teaching the source-based MA-course The League of Nations: international organisation, international politics and internationalism, 1850s-1950s at the Saxo Institute, University of Copenhagen (UCPH). As part of this course, with a small CEMES6 Grant in hand, and working as a researcher in Morten Rasmussen’s project Laying the Foundations – The League of Nations and International Law, 1919 to 19457 (UCPH, IRFD), I started to develop, test and teach prosopographical methodologies. As luck would have it, the UN Library and Archives in Geneva had at that point just finished digitising the personnel files – and even more amazing, they had made their own prosopographical database, where they had digitally extracted and ordered all sorts of biographical material from the files.

I now had on my hands two comprehensive sets of prosopographical data on the League employees – LONSEA and LONTAD – and all the digitised personnel files. This was an opportunity.

I hired an enthusiastic group of student aids – Natacha Bodil Ægidius Bengtson, Gry Lindgren Bach Kristensen, Lise Bødtker Sunde and Jonas Højbak Tilsted – and the computer science BA student Pelle Heigren (IT University) as a research assistant. We set to work – let’s say experimental work – trying to figure out how to use all this material. Some avenues proved very fruitful, others were dead ends. As it should be.

From this exploratory work, however, came a clear mission: How can we create a digital research tool and visualisation of the League Secretariat where scholars can select, combine and search on nationality, gender, age and position within any given time span as freely as possible? I had three concerns: (a) what was the reliability and quality of the prosopographical data; (b) what was the reliability and quality of the digital research tool; and (c) how could the user-friendliness and accessibility of the digital research tool be improved?

During the fall of 2021, computer scientist Obaida Hanteer at the Southern Campus Datalab (UCPH), Jonas Tilsted (continuing as a student aid) and I set about to develop the first prototype of VisuaLeague. I was at the time a Gerda Henkel Fellow, with a project on “European Security in a Changing World: General disarmament between international organisations and state sovereignty, 1890s-1930s”, and this prosopographical work was an integral part of the research process.8

We further developed it the spring 2022. I had been lucky enough to receive some internal UCPH funding for a so-called research-based teaching experiment for a “network-based analysis of the League of Nations Secretariat”.9 Obaida and Jonas were joined by Xiaoyu Shi, a computer science MA student from the Department of Computer Science (DIKU, UCPH). Our little team introduced the students to network analysis (with the tool Gephi10), based on our prosopographical work, and we encouraged the students to use and test VisuaLeague as part of their exams. By the end of the semester, we not only had some excellently researched and innovative exam papers, but also a thoroughly tested and well-designed digital research tool.

During the fall of 2022, we brought in Yuan Chen, at the time an MA student at the Department of Computer Science (DIKU, UCPH). Chen was a crucial member of the team: Building on our previous work, he essentially coded the final version. Jonas and I were simultaneously checking, updating and double-checking all the prosopographical data. And early versions of the digital tool were tested with the help of external partners – historians with expertise on the League of Nations12. At the same time, we also developed a so-called Research Guide on the League of Nations Secretariat for the UN Library and Archives website, with contributions from some of the best historians in the field. VisuaLeague was finally published on March 1st 2023 and is an embedded element of this Research Guide13.

VisuaLeague – a digital meta-project

I cannot speak intelligently about the coding – this was the wheelhouse of Obaida and Yuan – but I can attest to the quality of the prosopographical dataset. And as the saying goes: you’re only as good as your data.

Essentially, we had a fantastic starting point with the LONSEA dataset. The genius of this dataset, apart from the fact that someone made it, was that it contained just about every employee of the League Secretariat. What is more, creators of LONSEA had chosen to make a new entry into the excel sheet for each new contract. This might seem like a detail, but it meant that you could trace the temporal movement of each person. Each new contract (whether they were promoted, renewed or moved to a different section) was a separate entry, with a starting date and end date. We could thus follow every individual through the time they worked in the Secretariat.

But, LONSEA was made by humans, in many cases students poring over personnel files. Mistakes were made, names were misspelled, employment categories misunderstood, and entries were left empty. This is not in any way a criticism, but it meant that the dataset had room for improvement. This is where the LONTAD dataset came in very handy: it had more, and more precise, information about all the employees. It was, however, less structured, and only had one entry per employee. In other words, it did not have the temporal aspect. So, we kept the ingenious structure of the LONSEA dataset, and checked, corrected and upgraded it with the LONTAD dataset. If there were inconsistencies between the two datasets, we went to the source: the personnel files. This was a cumbersome process, and there are certainly still mistakes in the dataset, but inch by inch, entry by entry, we worked towards getting the best possible quality. Here I must thank Jonas Tilsted, for remarkably consistent and patient work.

We might say that VisuaLeague is a sort of digital meta-project, which connects, systematises and enhances existing digital projects, tools and resources. In a recent conversation in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society entitled “What is Digital Global History Now?”, I argue that we need more of these kinds of digital projects, which draw on existing work: “Imagine, for instance, such a meta-project where one could connect prosopographies of employees across international organisations, opening the possibility to write truly global (social, institutional, diplomatic, etc.) histories of twentieth century-international administrations. Building on such meta-projects, future research projects would have the possibility both to document macro-patterns in developments across time/space and to connect these to refined studies of actors and agency”.14 Working like this, we can avoid what so often happens: once a project ends, its digital output becomes an increasingly buggy relic of the past.

Why did we make VisuaLeague?

Now, the fundamental question is what is a prosopography good for? Why is it useful to have a digital prosopographical research tool when researching the League of Nations?

Well, through prosopography – or standardised collective biographical data – you get a systematic overview of the traits of any given social group, such as gender, nationality, age, education, position etc., which is then mapped on to the organisational structure and chronological development of the institution.15 As an important methodology within social history, then, prosopography allows us to “attack two of the most basic problems in history”: how to uncover deeper interests, social and economic affiliations, and the roots for action among actors; and how to reveal social structures and social mobility within groups over time.16

These prosopographical and biographical approaches, in turn, should then be coupled with an analytical sensitivity towards the institutional landscape in which this agency was placed. The League Secretariat was founded upon principles of functional division of labour and international loyalty, but equally structured by more or less formal hierarchies of power-knowledge, ideology, nationality, gender, class, generation, race, and civilization.17

When we investigate the employee’s freedom and capacity to act, we therefore need to consider it as functionally and spatially specific and as nested in the multiple structuring hierarchies of the organisation. But we also need to appreciate the staff of the League as creators of these very bureaucratic structures: the printers, working day and night during the gigantic World Disarmament Conference (1932-34), for instance, got more manpower and more humane deadlines, when one of the duplication operators demanded change in a written note to his superior – this small complaint changed how the entire multilateral conference was serviced. We are thus trying to capture interplay between (institutional) structures and what we could call ‘situated’ agency.18

The prosopography, in this context, becomes the ‘meso-level’ in a historical analysis, connecting the ‘micro-level’ of individuals and their words and deeds and the ‘macro-level’ of for instance a policy field, set of institutions or mode of governance. This allows for a ‘vertical’ reading of an international organisation, across the macro, meso and micro-level. It also allows for a ‘horizontal’ reading, connecting people, practices and ideas across and between international organisations. The prosopographical data allows you to ‘discover’ communities, roles and discourses across institutional landscapes, which you in turn can explore and interrogate; it also allows you to situate and qualify, in this instance administrative agency in an international, institutional and inter-personal setting. This is why prosopography is an essential part of INNER_LEAGUE’s approach.

What might VisuaLeague 2.0 include?

So, finally, what might a VisuaLeague 2.0 look like? We have, in short, three ambitions: first, we would like to map, categorise and add a variable in the dataset on the educational and professional background of as many employees as possible. Unlike, say, nationality, this requires more of a qualitative, analytical judgement, because we need to create consistent categories of employment/education for us to be able to see any meaningful patterns. But it should be worth it: if we can trace educational and professional tendencies across time and institutional space, we can understand the formation of bureaucratic communities and hierarchies in a completely new way.

Second, we still have to answer the question of where all the employees went after they worked for the League of Nations. Several groundbreaking studies, by historians like Myriam Piguet and Jane Mumby, have contributed important pieces to this puzzle. We essentially want to find as many of the still missing pieces as possible – it might never be complete, but it will be an important contribution to our understanding of the impact and legacy of the League’s particular brand of institutionalised multilateralism. It could also be the beginning of an even broader effort, which could connect prosopographical data from several international organisations (as alluded to above).

Finally, we want to visualise both the institutional geography of the League Secretariat and the geographical spread of its employees. We would want to create an interactive and chronological organogram of the Secretariat, which would make it much easier for researchers to understand where officials and staff worked and what relationship a given section or department had to the rest of the organisation. And we would want to create a chronological and interactive map of the global make-up of the Secretariat.

Looking back on the making of VisuaLeague, I know that we are at the beginning of a long journey – and that there will be many surprises waiting for us.

- https://visualeague-researchtool.com

- About the LONTAD project: https://libraryresources.unog.ch/lontad ; the digital archives: https://archives.ungeneva.org/lontad

- Madeleine Herren, Christiane Sibille and Christoph Meigen (eds.), Searching the Globe through the Lenses of the League of Nations: Database, http://www.lonsea.de

- https://projects.au.dk/inventingbureaucracy

- For an overview of publications, see here: https://projects.au.dk/inventingbureaucracy/publications

- https://cemes.ku.dk

- https://internationallaw.ku.dk

- https://www.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de/en/european-security-in-a-changing-world-general-disarmament-between-international-organization-state-sovereignty-1890s1930?page_id=123176

- https://internationallaw.ku.dk/news/new-grant/

- https://gephi.org

- Several of these exams were worked into a special issue for Culture and History – Student Research Papers during the fall of 2022 and spring of 2023: https://tidsskrift.dk/culturehistoryku/issue/view/10109

- Ikonomou, H. A., Chen, Y., Hanteer, O., & Tilsted, J. (2023). Visualizing the League of Nations Secretariat - A Digital Research Tool: Visualizing the League of Nations Secretariat - A Digital Research Tool. Computer programme, . https://visualeague-researchtool.com/. For an overview of the whole team, see: https://internationallaw.ku.dk/research-projects/visualizing-the-league-of-nations-secretariat--a-digital-research-tool/

- https://libraryresources.unog.ch/LONSecretariat/home. This research guide included curated contributions from Karen Gram-Skjoldager, Haakon A. Ikonomou, Torsten Kahlert, Myriam Piguet, Emanuele Podda, Morten Rasmussen, Jonas Tilsted, Emil Seidenfaden, Martin Grandjean, Hannah Tyler and Jane Mumby. It was edited by Hermine Diebolt, Jonas Tilsted and Haakon A. Ikonomou.

- Toye, Richard, Astrid Swenson, Haakon A. Ikonomou, Robert Lee, Cassandra Mark-Thiesen, and Jessica M. Parr. “What Is Digital Global History Now?” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 2025, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0080440125000064.

- Seidel, Katja, The Process of Politics in Europe: The Rise of European Elites and Supranational Institutions (London, I.B. Tauris, 2010); Mourlon-Druol, Emmanuel, “Less than a Permanent Secretariat, More than an Ad Hoc Preparatory Group: A Prosopography of the Personal Representatives of the G7 Summits (1975-1991)”, Emmanuel Mourlon-Druol and Federico Romero (eds.), International Summitry and Global Governance: The Rise of the G7 and the European Council, 1974-1991 (Basingstoke: Routledge, 2014), 64-98; Tollardo, Elisabetta, Fascist Italy and the League of Nations, 1922-1935 (London: Palgrave, 2016); Fritz, Vera, “Judge Biographies as a Methodology to Grasp the Dynamics inside the CJEU and Its Relationship with EU Member States”, Mikael Rask Madsen, Fernanda Nicola, and Antoine Vauchez (eds.) Researching the European Court of Justice: Methodological Shifts and Law's Embeddedness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 209–34; Kahlert, Torsten, “Pioneers in International Administration: A Prosopography of the Directors of the League of Nations Secretariat” New Global Studies, 13(2), (2019), 190-227.

- Stone, Lawrence, “Prosopography” Daedalus, 100, 1, (1971), 46-79, 46. See also: Keats-Rohan, Katharine S. B. (ed.), Prosopography Approaches and Applications: A Handbook, Prosopographica et Genealogica 13 (Oxford: P&G, Prosopographica et Genealogica, 2007).

- Ranshofen-Wertheimer, Egon F., The International Secretariat of the Future: Lessons from Experience by a Group of Former Officials of the League of Nations (London/New York: The Royal Institute of International Affairs Oxford University Press, 1944); Giraud, Emile, “Le secrétariat des institutions internationales (Volume 79)”, Collected Courses of the Hague Academy of International Law (1951); Dykmann, Klaas, “How International was the Secretariat of the League of Nations”, International History Review, vol. 37/4, (2015), 721-744; Gram-Skjoldager, Karen & Haakon A. Ikonomou, “The Construction of the League of Nations Secretariat. Formative Practices of Autonomy and Legitimacy in International Organisations”, The International History Review, 41:2, (2019A), 257-279.

- Drawing here on sociologist Norbert Elias’ notion of ‘figurations’: Elias, Norbert “Homo clausus and the civilizing process” in Paul du Gay, Jessica Evans and Peter Redman (Eds.) Identity: A Reader, (London: Sage Publications, 2000), 284-297.