Clinging to the past? Let’s overcome the fear of the digital

Blog post by Jonas Tilsted

History, as an academic field, lags behind other fields regarding the use of digital research tools.[1] In a field that emphasises qualitative approaches, some historians even criticise the use of the tools, partially because they adopt a quantitative approach.[2] This blind rejection of digital tools risks historians losing out on methods that substantially assist research. Historians clinging to the past endangers the field of falling behind when it comes to producing up-to-date knowledge. Using digital tools is part of what can be called digital history, which is part of a larger ‘digital turn’ in academia. Digital history encompasses a wide array of things that are too plentiful for me to describe in detail in this short post.[3] I argue that we are all doing digital history to some extent; I don’t know of many, if any, historians who don’t use digitised sources or do keyword searches when looking for sources or material. This is possible because of the digitisation of the material, the inventory of the archive, or a description of the material.

Despite being part of the digital turn, historians have not embraced the possibilities to their full extent. In this post, I elucidate some of the possible insights when using digital text-mining tools while pointing to some of the challenges of employing the tools and ways of overcoming the challenges. I do this by explaining my current PhD project at the European University Institute. Here, I employ digital text-mining tools to study the League of Nations Council. Through this explanation, I aspire to show that fully embracing the digital turn is not as scary as it seems. It can help fill out knowledge gaps and elevate research.

What I hope to show in my project

After the devastations of the First World War and following the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the victors created the League of Nations and its Council to secure world peace and effective disarmament of the world. The League consisted of three main organs: the Secretariat, the Assembly, and the Council. The three organs can be compared to a national political entity; the Council is comparable to an executive government, the Assembly to a parliament, and the Secretariat to the civil service behind the two.[4] I have previously argued that the Council adapted dynamically to the challenges that it met and to the internal battle for power it had with the Assembly.[5] The Council was able to take the executive role because it had relatively few rules and a loose formal structure. In my project, I study the discussions at the Paris Peace Conference on the creation of the Council, what it was supposed to do, and whether this loose structure was a result of a conscious decision. I observe how the Council created their own framework and procedures and how the Council structured itself without having any framework to build upon.

Further, I examine the Council’s methods, functions, and procedures. For this purpose, I adopt a mixed-method approach that incorporates digital research tools and traditional close-reading of the sources. The implementation of digital research tools allows me to uncover traits and patterns that would not be possible if I only used traditional methods – this approach will be explained in more detail later. I hope to be able to identify whether the Council employed specific types of methods to deal with specific types of conflicts. I do this through minor case studies of conflicts spread over time and type. The case studies will contextualise the methods and procedures that I identify using the digital tools. Simultaneously, the case studies show how the methods worked in practice.

The Council’s purpose was to maintain world peace and to look out for the world’s general interests. However, the Council consisted of representatives from member states who had national interests to look out for. I explore the struggle between the national and international interests in the Council and its effect on the way it dealt with conflicts. The League and the Council were attentive to publicity and openness; [6] thus, a representative would, I suspect, not be able to openly fight for national interests if they were contradictory to international interests. I examine how representatives navigated this dilemma. Further, the Council gained legitimacy and power through establishing itself as a mediator between states and by dealing with conflicts in a good and objective way.[7] I study whether the struggle between national and international interests impaired the Council’s legitimacy, position, and ability to deal with conflicts.

I incorporate a Bourdieuisian field theory approach to examine both the Council’s internal dynamics and the external relations with other League organs, international organisations, and member states. This places the Council in a larger field of international diplomacy and politics. International relations (IR), among other fields, has increasingly adopted Bourdieu’s field theory. IR scholars have used this approach as part of the “practice turn”[8] to overcome the challenge of the structure/agent dilemma; whether agents’ actions are fundamentally determined by the social structures or if agents have agency and can affect the structures of society. Field theory helps overcome this dilemma qua its view on the two aspects as interdependent and mutually structuring and structured. It can also help me understand why some representatives had more power in the Council, what the representatives could and did do to obtain power, and how and why the Council was structured as it was. This approach also removes the focus from states as the primary actors on the stage of international diplomacy, which has previously been the dominant view.[9] Instead, I see individuals as the primary actors. It can further help us understand the international world in which the Council operated and how the Council had influence on other organisations or League organs, while at the same time, the other actors could influence the Council and their decisions.

What is missing from digital history today?

Whilst the great majority of historians are doing digital history in some regards, the great majority of historians don’t do what can be termed computer-assisted research, digital research tools, or digital methods.[10] Many historians have done important work using different methods and tools: Emmanuel Mourlon-Druol and Enrico Bergamini have used text-mining and network analysis to illustrate new facets of the establishment of the euro.[11] Further, in Emmanuel Mourlon-Druol’s project, EUROCON, he incorporates network analysis to explore European policymakers’ views on how to make the organisation of the European Economic Community fit for the creation of a single currency.[12] Torsten Kahlert has displayed the benefits of prosopography by using the method to uncover traits of the Secretariat that would be difficult to map otherwise.[13] Martin Grandjean, a pioneer in historical social-network analysis and visualisation, has applied social-network analysis and the tool ‘Gephi’ to examine the divide between Paris and Geneva in the interwar years.[14] The creation of the tool VisuaLeague, by Haakon A. Ikonomou, myself and several other people as a research tool, that can be used in many ways and for several types of inquiries, shows that historians are doing digital work benefiting others.[15] VisuaLeague is additionally an example of interdisciplinary work between historians and computer scientists. The use of digital tools is not only present in the field of international organisations, but it is the field in which I move, and thus, have the largest frame of reference.[16]

Even though significant work is being done and has been done with digital methods, more can and should be done. This is supported by the of example Oxford’s undergraduate history program which doesn’t have anything on digital methods,[17] and that at a common room conversation on the state of global digital history between Richard Toye, Astrid Swenson, Haakon A. Ikonomou, Robert Lee, Cassandra Mark-Thiesen, and Jessica M. Parr discussions about computer assisted research and specific digital methods were limited to mentioning a program called Sketchfab and the aforementioned tool, VisuaLeague;[18] one could be excused if, after reading the conversation, one had the idea that digital methods are only one thing – which is definitely not the case. An almost indefinite number of digital tools and methods that can be employed to do historical research exist.

Challenges when using digital methods

Dangers and challenges do exist when one is using digital tools for distant reading and text mining. The first is that not everything in an archive is available, and the archive may be incomplete. Thus, you can’t assume your data is complete. Knowledge about the archive and its content can help overcome this challenge.[19] The incomplete data is likewise a problem for ‘traditional methods’; nevertheless, distant reading enhances the problem since the material is not read from one end to the other, which could have indicated that something was missing. The second challenge is that one risks losing the context of the material. Due to the digitisation of the material, historians do keyword searches, thereby not having to read through a whole file to find what one is searching for.[20]

A third challenge is that some try to do too large generalisations from too small a dataset. Some scholars perceive the digital tools as being more capable than they are and, thus, they seek to use the tools to answer too large questions. One must continue to think, analyse, and interpret like a historian. This can diminish the wish to ask your dataset too large questions that it can’t answer.[21]

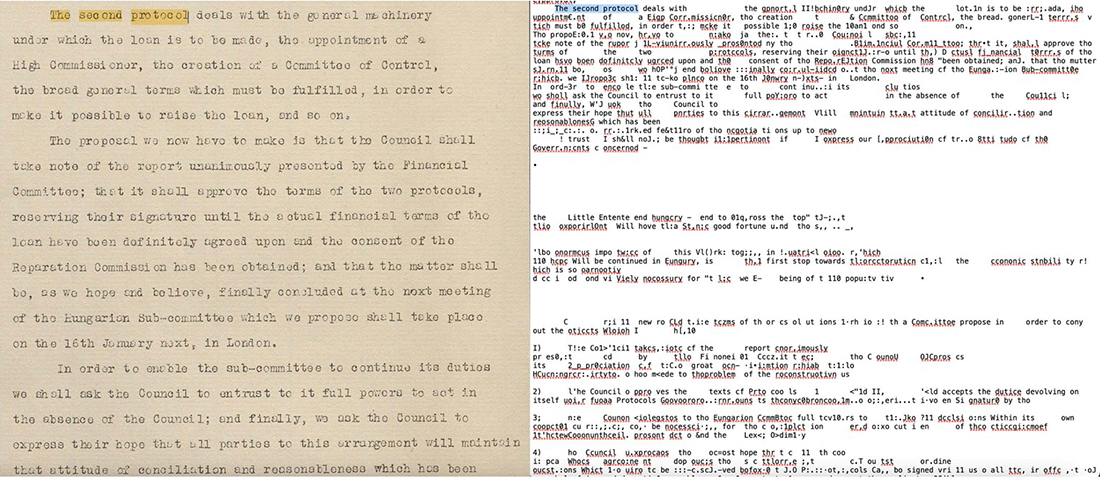

The last challenge, I will mention, is “dirty data”. This is typically a result of bad scanning or the optical character recognition (OCR) “mis-reading” a word or letter, ex. If “n” gets read as “m”. This might seem innocent, but if it happens a lot throughout a file, it can cause meanings or important facts to be lost in the process.[22] Figure 1 illustrates an extreme example of problematic OCR-scanning. Programs for cleaning data do exist, and it is possible to get rid of some misreadings; however, one can’t be sure if all mistakes are gone unless all the material is read through. This would defeat the purpose of the digital tools, and this challenge must be accepted; luckily, OCR is getting better, especially at dealing with old texts.

What I do

I utilise digital text-mining tools to analyse the minutes of the League of Nations Council’s 107 sessions from 1920-1939.[23] This can uncover new patterns in Council decisions, deliberations and discussions. The digital tools can’t stand alone in an analysis. To contextualise the findings from the digital tools, a close reading of the sources is necessary. In this project, I thus apply a mixed-method approach integrating quantitative digital text-mining tools with traditional historical close reading and case studies. This approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of both micro and macro-level dynamics and changes within the Council.

The distant-reading tools that I employ utilise a form of word counting that some historians have been doing manually for hundreds of years, although the tools can do it much faster.[24] When employing tools that utilise word counting, one uses keywords, whilst the tools produce keywords specific to the corpus – a set of texts. When choosing which words are significant and how to interpret them, knowledge of the field in which you are working is necessary. This ensures that words that have no significance are not given meaning and effect on the corpus. Here, it is important to note that the tools can’t read words or sentences. They merely attach a statistical value to the words and can show which words are statistically meaningful. A word can, for example, have high statistical value if it appears a lot in some part of the corpus but not in the rest. The tools, moreover, use large language models (LLMs) to determine if a word has statistical value in relation to ‘normal’ language. However, most LLMs are based on modern language, and historical words or language norms can be assigned statistical value despite being normal at the time of the material.

Whilst a word can be a keyword with statistical meaning, it doesn’t mean that it is significant for a historical analysis. To ascertain whether a word has value for the analysis, it is essential to combine the distant reading with a close reading of the material. This mixed-method approach yields the best results, and by obtaining knowledge of the context, it can help tackle some of the challenges that I presented earlier. It will moreover help get rid of “false positive” results; times when the tool shows keywords which may not be meaningful for the analysis, or where the word may have been used in another way than expected. The importance of utilising the mixed-method approach is backed by the fact that digital text-mining tools’ capabilities are predominantly in showing general aspects of the corpus, whilst the reading can confirm the general aspects. This way, one can find patterns in the corpus with the digital tools and confirm them as meaningful for an inquiry and not changes in speech/writing patterns.

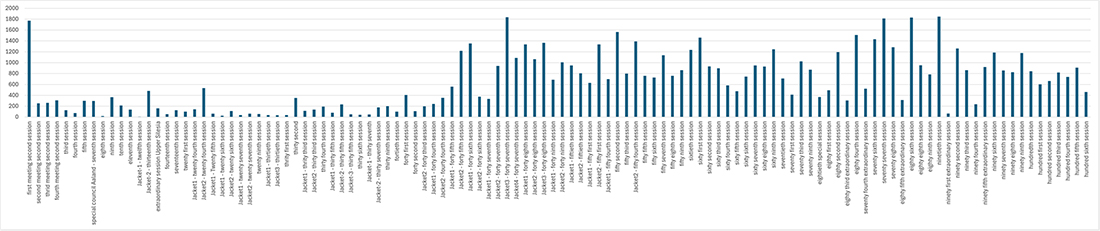

The mixed-method approach can be exemplified by a finding from my earlier work.[25] I found that the Council, through time, increasingly employed the rapporteur as a method. The rapporteur was a member of the Council tasked with gathering information about a conflict or dispute and then bringing a proposal to the Council about how to proceed with the conflict.[26] Sometimes the proposal had the character of a solution. Figure 2 shows the normalised frequency of the word “rapporteur” by each session it appears in spanning the whole period of the Council, 1920-1939. The word does not appear in all sessions; thus, not all 107 sessions are present in the figure. To validate whether this was an outcome of a change in the use of rapporteurs or a consequence of speech patterns, I closely read the instances where the word was used, revealing that the Council increasingly employed the rapporteur to handle conflicts. The increasing use of the rapporteur can be seen as an effect of more complicated conflicts being handled by the Council. Qua the complicated character of the conflicts, the Council needed more information.

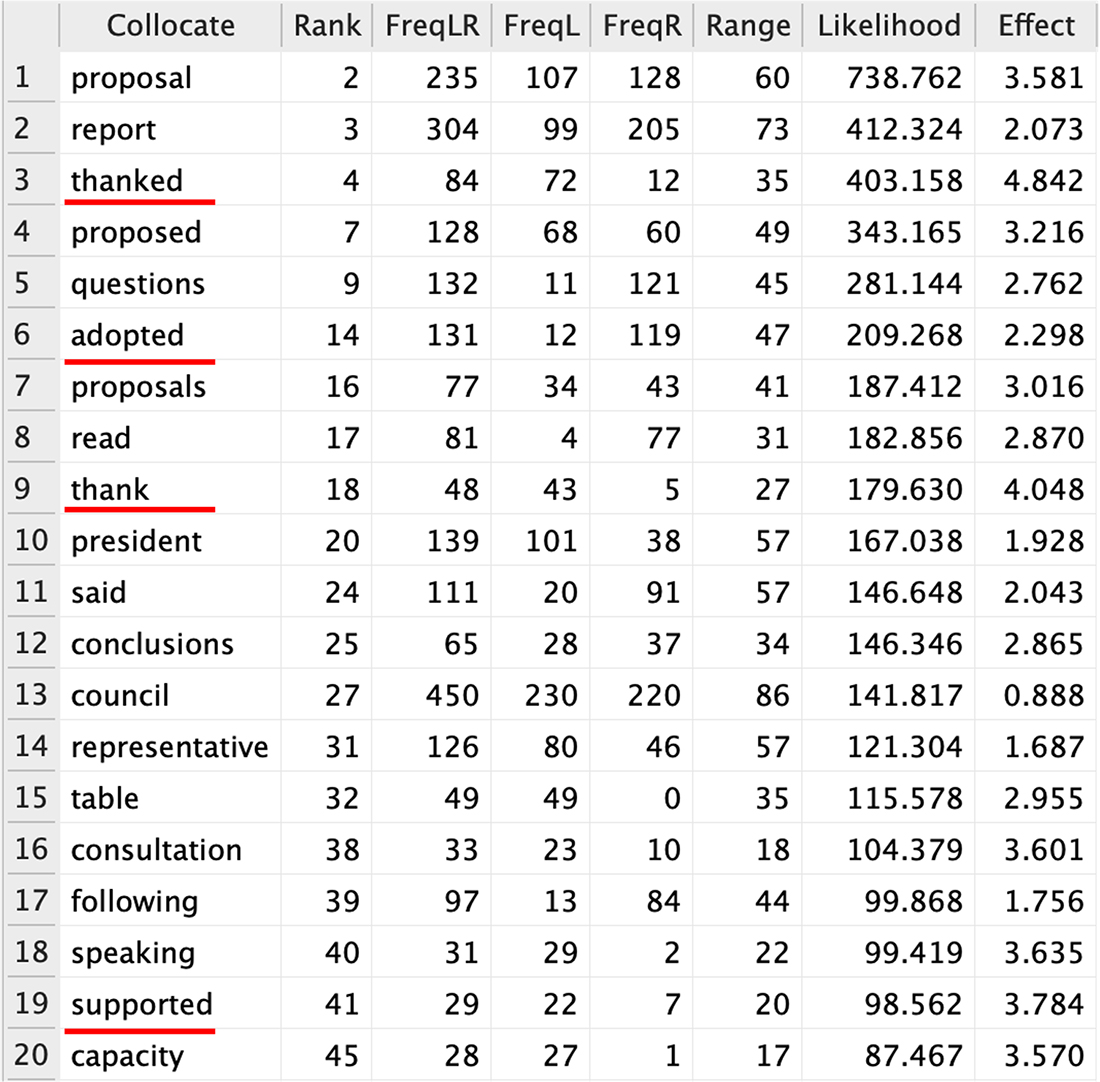

To further examine the role of the rapporteur in the Council, I did a collocate search on the word rapporteur, showing the words that frequently or in a statistically meaningful way were related to the keyword. This revealed that no negative words were related to the rapporteur, which can be seen in Figure 3. Positive words like “thanked”, “adopted”, “thank”, and “supported” were all statistically close to the word. A close reading disclosed that “thanked” and “thank” were a result of a norm in the Council. Whenever a rapporteur accepted a task or presented a report or a proposal, he would be thanked by several members of the Council. These words were, thus, not of any importance to my inquiry, as they were not a product of a change in the way the Council employed the rapporteur or the work of the rapporteur, but a product of a speech pattern in the Council.

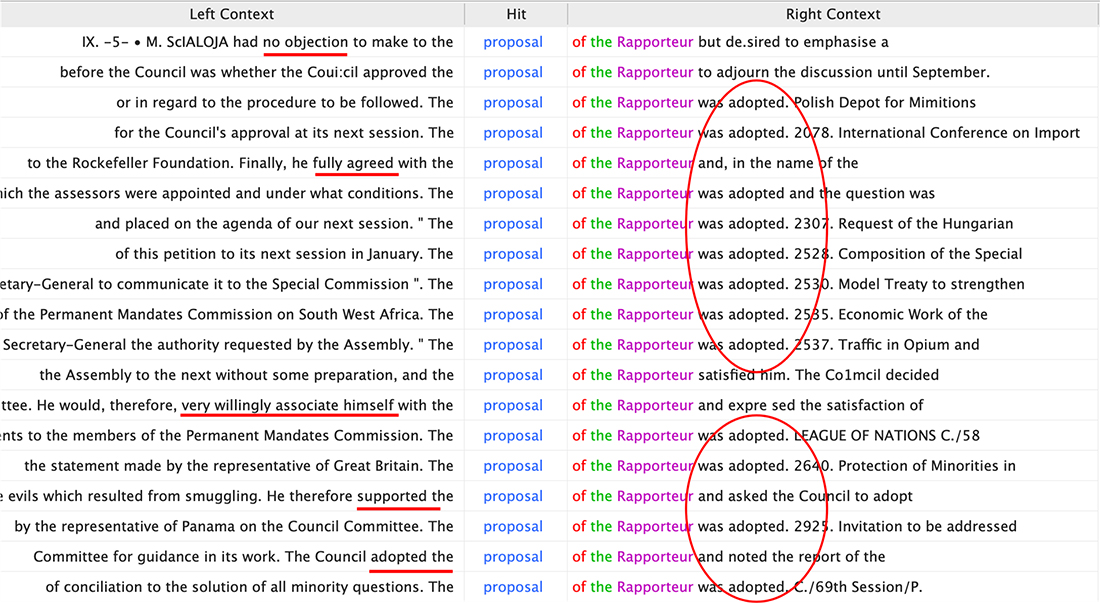

A close reading of the times when rapporteur and proposal were used together demonstrates that when a rapporteur proposed, it was typically accepted, agreed to, supported, or adopted. An example of this tendency can be seen in Figure 4. This indicates that despite the rapporteur having no formal decision-making abilities, the practice of the Council ensured that they had a degree of quasi-decision-making abilities – provided that the proposal was within the boundaries of the Council’s doxa/norm.

This brief example of how one can work with the mixed-method approach elucidates how advantageous it can be to employ digital tools in historical research by pointing to three key benefits of the digital tool employed for this study. First, the increasing use of the word rapporteur would have been difficult to notice if all 107 sessions of the Council were closely read. Additionally, the tools make the findings more tangible. Second, the results from the collocate search would be very time-consuming, and the manual counting of words is hardly feasible for any regular project. Third, the easy access to all 235 times rapporteur and proposal was used together made it easier to confirm trends and results than if one were to flip through sessions looking for times when the proposal was evaluated. The brief example has illustrated how close reading and distant reading complement each other.

My aim with this blog has been to argue that we, as a field, should not look away from the possibilities that embracing the digital turn can provide. My aim has not been to claim that using digital methods produces better research, like using traditional historical methods doesn’t produce better research. A combination of the two can nonetheless provide better research. The gulf between the two approaches needs to be overcome. This will open new paths to already researched topics and questions, it will pave the way for answering existing questions that may have been impossible to answer before, and it will open avenues for new questions and projects. I don’t want to call out those who don’t use digital methods. I merely want to point out the possible advantages of using them. I applaud the process of creating a VisuaLeague 2.0 as it will, I am quite certain, be a valuable tool for future inquiries. Furthermore, it is embracing the digital turn in all its aspects. Hopefully, it will be part of a movement that can pave the way for more focus on the digital and the interdisciplinary outlooks that the digital turn allows for, while highlighting the potential new avenues of research created by the digital turn.

-----------------------------------------------

[1] Ian Milligan, The Transformation of Historical Research in the Digital Age, 1st ed., Cambridge Elements. Elements in Historical Theory and Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 7; Luke Blaxill, ‘Why Do Historians Ignore Digital Analysis? Bring on the Luddites’, The Political Quarterly (London, 1930) (Oxford, UK) 94, no. 2 (2023): 279, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13267.

[2] Blaxill, ‘Why Do Historians Ignore Digital Analysis?’; Jo Guldi, The Dangerous Art of Text Mining: A Methodology for Digital History, First edition. (Cambridge University Press, 2023), xviii–xxii.

[3] For a wider description of what digital history encompasses, see: Mats Fridlund et al., Digital Histories: Emergent Approaches within the New Digital History (HUP, Helsinki University Press, 2020).

[4] League of Nations Secretariat, Ten Years of World Co-Operation (Secretariat of the League of Nations, 1930), 11–15.

[5] Jonas Tilsted, ‘Diplomati Og Magtkampe i Mellemkrigstiden: En Analyse Af Folkeforbundets Råds Konflikthåndtering Og Rådet Som Transnational Felt, 1920-1939’ (MA-thesis, SAXO-Institute, University of Copenhagen, 2024).

[6] Tilsted, ‘Diplomati Og Magtkampe i Mellemkrigstiden: En Analyse Af Folkeforbundets Råds Konflikthåndtering Og Rådet Som Transnational Felt, 1920-1939’.

[7] Karen Gram-Skjoldager and Haakon A. Ikonomou, ‘Making Sense of the League of Nations Secretariat – Historiographical and Conceptual Reflections on Early International Public Administration’, European History Quarterly (London, England) 49, no. 3 (2019): 431–32, https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691419854634; Tilsted, ‘Diplomati Og Magtkampe i Mellemkrigstiden: En Analyse Af Folkeforbundets Råds Konflikthåndtering Og Rådet Som Transnational Felt, 1920-1939’.

[8] See, for example, Theodore R. Schatzki et al., The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory (Routledge, 2001); Rebecca Adler-Nissen, Bourdieu in International Relations: Rethinking Key Concepts in IR, The New International Relations. (Routledge, 2013); Christian Bueger, International Practice Theory, 2nd ed. 2018., with Frank Gadinger (Springer International Publishing, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73350-0.

[9] Alexandru Grigorescu, ‘State Participation in the League of Nations Council and UN Security Council: Successful vs. Unsuccessful Reform Efforts’, in Historical Institutionalism and International Relations: Explaining Institutional Development in World Politics, ed. Thomas Rixen et al. (Oxford University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198779629.003.0005; Zara Steiner, The Lights That Failed: European International History, 1919-1933, Oxford History of Modern Europe. (Oxford University Press, 2005).

[10] Richard Toye et al., ‘What Is Digital Global History Now?’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 24 March 2025, 1, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0080440125000064.

[11] Emmanuel Mourlon-Druol and Enrico Bergamini, ‘Economic Union in the Debates on the Creation of the Euro: New Evidence from the Tapes of the Delors Committee Meetings’, Journal of Digital History 2, no. 1 (n.d.), https://doi.org/10.1515/JDH-2023-0008?locatt=label:JDHFULL.

[12] Emmanuel Mourlon-Druol, ‘EURECON Project Presentation’, Emmanuel Mourlon-Druol, 23 September 2016, https://www.e-mourlon-druol.com/eurecon/.

[13] Torsten Kahlert, ‘Prosopography: Unlocking the Social World of International Organizations’, in Organizing the 20th-Century World (Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2020), https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350136687.ch-004; Torsten Kahlert, ‘Pioneers in International Administration: A Prosopography of the Directors of the League of Nations Secretariat’, New Global Studies (Berlin) 13, no. 2 (2019): 191–228, https://doi.org/10.1515/ngs-2018-0039.

[14] Martin Grandjean, ‘The Paris/Geneva Divide’, in Culture as Soft Power: Bridging Cultural Relations, Intellectual Cooperation, and Cultural Diplomacy, ed. Elisabet Carbó-Catalan and Diana Roig Sanz (De Gruyter, 2022), https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110744552-004/html.

[15] For a more comprehensive description of the tool and its possibilities, see: Haakon A. Ikonomou et al., ‘Visualizing the League of Nations Secretariat - a Digital Research Tool’, Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen 2023, https://visualeague-researchtool.com/; Or this blog post about the creation of the tool and its functions and usability: Haakon A. Ikonomou, ‘Making VisuaLeague’, University of Copenhagen, 26 September 2025, https://saxo.ku.dk/innerleague/about-the-project/research-blog/blog/making-visualeague/.

[16] An example of a huge project that employs digital thinking outside the field of IOs is the project Link-Lives, which created a digital research tool; ‘Om projektet Link-Lives’, Link-Lives, n.d., accessed 27 October 2025, https://link-lives.dk/om-projektet/.

[17] Blaxill, ‘Why Do Historians Ignore Digital Analysis?’, 287.

[18] Toye et al., ‘What Is Digital Global History Now?’

[19] Guldi, The Dangerous Art of Text Mining.

[20] Putnam, ‘The Transnational and the Text-Searchable’.

[21] Guldi, The Dangerous Art of Text Mining.

[22] Milligan, The Transformation of Historical Research in the Digital Age, 21.

[23] The digital methods in my project have been made possible by the LONTAD project, which digitised the archives of the Secretariat, which also held minutes from the Council meetings.

[24] Guldi, The Dangerous Art of Text Mining, 101.

[25] Tilsted, ‘Diplomati Og Magtkampe i Mellemkrigstiden: En Analyse Af Folkeforbundets Råds Konflikthåndtering Og Rådet Som Transnational Felt, 1920-1939’.

[26] Secretariat, Ten Years of World Co-Operation, 14.