"A Result of the World Cataclysm of War and Revolution"

Fieldnotes, Observations and Testimonies from the League of Nation’s Investigation of Trafficking within the Russian Refugee Communities

Blog post by Sebastian Vang Jensen

In late 1932 the League of Nations released a report uncovering the world of, what today would be termed, human trafficking throughout the Asian continent. The report featured a detailed exposé of the complex social problem facing the so-called White Russian diaspora, following the Russian Revolution, and its effect on trafficking in the region. [1] Along with the official report, the League’s archive in Geneva holds all the unreleased observations, testimonies and materials the report was based on. This text is a tour down these digital archival folders, following in the footsteps of these researchers, and situating their work within the social fabric of the Russian diaspora they investigated. The purpose is to unearth the lived realities of the people they encountered and elaborate on how the knowledge of these communities pushed the League’s experts to rethink the causes driving this regional movement of bodies and services.

The Commission

On the 9th of October 1930, a small League-appointed research delegation, called the Travelling Commission, stepped aboard a steamship in Marseille, embarking on a grand international investigation into the trafficking in women and children throughout Asia. The scale of this enquiry was vast, covering most of what was at the time called the Near, Middle and Far East. [2] It was the second of its kind; the first one had focused on trafficking in Europe and the Americas. These investigations have been described as the first ever social-scientific studies of a global social problem, [3] and were a product of the League’s official entrustment of anti-trafficking, going back to its formation. During this period the modern concept of trafficking emerged from the earlier campaigns against the so-called white slave trade, and it was under the League’s auspices that this category was universalized and codified and that anti-trafficking efforts institutionalized. [4] These investigations into international trafficking reflect a wider organizational belief in transforming international politics through science, evidence and dispassionate objectivity. [5]

The area covered was, in contrast to the previous investigation, characterized by varying degrees of imperial control and the commission was pressured, by both national governments and imperial powers, to consult only official government sources. [6] However, during their travels through China and Manchuria the commission began to unearth the harsh realities of the White Russian diasporic communities scattered throughout the region. The conditions of the displaced Russian communities meant that the commission relied heavily on unofficial sources, which means that we today have considerable accounts “from below” covering this part of the campaign.

The commission consisted of three official expert appointees: Chairman of the Commission, Bascom Johnson, an American Lawyer, who had played a leading role in the previous investigation. The second member was Swedish doctor Alma Sundquist, a specialist in venereal diseases, sexual educator and avid social activist and women’s rights campaigner. The third member was Karol Pindor, a Polish career diplomat who had spent over 25 years working in various diplomatic positions in China. The official delegates were accompanied by two members of staff, Secretary M. W. von Schmieden, German national and employee of the League's Secretariat, and British Stenographer, C.E. Marshall. This party of five would spend the next 18 months travelling across Asia collecting and analyzing data on trafficking and prostitution.

Unofficial Knowledge

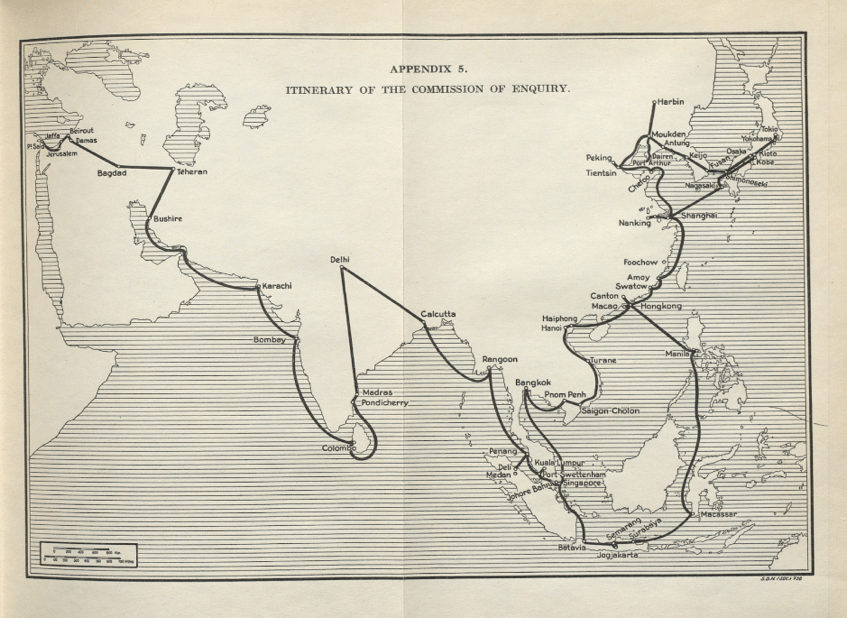

Itinerary of the Travelling Commission, Enquiry into Traffic in Women and Children in the East - Report to Council, Appendix 5. League of Nations Archives, Geneva.

My previous work on the League’s trafficking enquiries focused on their construction and framing of the problem, and how they shaped discourses around race, sexuality, morality and humanitarianism. [7] This approach privileges the official knowledge constructed by the experts in their reports and recommendations. Going back to the League of Nations Archive, I was struck by the abundance of unofficial voices and perspectives in the many testimonies, letters, field reports and interviews conducted by the commission. Inspired by scholarship emphasizing the quality of these unofficial records, when trying to get closer to the lived realities of trafficked people and traffickers, [8] I set out to retrace the steps of the Commission's work with the Russian diaspora, in the cities of Shanghai and Harbin. In doing so I hope to highlight the role of the unofficial accounts and present a decentralized account of how this report came to be, by exploring the dialogical encounters between the League’s experts and members of these communities.

Sounding the Alarm

After years of civil war, revolution and warlordism, The Chinese Republic had recently been reunified under a nationalist government. China’s political landscape remained unstable and divided, with great international port cities still marked by extensive Western extraterritoriality. These were divided into various settlements and concessions, where the great imperial powers exercised their influence. [9] The commission estimated that around 120.000 Russians were residing in China and Manchuria at the time of their investigation. [10]

This group consisted of refugees, exiles and pre-revolution residents, all being cut off from their regular sources of income, due the effects of the Russian Revolution and ensuing civil war. [11] These complex geopolitical dynamics driving the migration from Russia to China, led the Commission to: “(…)call special attention to the urgent necessity of preventive work among the young women of the Russian refugee communities in China.” [12]

Newspaper cutout: the Travelling Commission at a formal event. The Tribune Manila, Jan. 28, 1931. League of Nations Archives, Geneva.

Initially, the scale and severity of the problem do not appear to have been on the commission’s radar. Instead, this came about gradually due to information obtained throughout their time in China. Looking at a preliminary field update from von Schmieden, it seems clear that the information on the gravity of the situation arose out of unplanned contacts within these diasporas established during the tour. [13] This, and the final report, show that these communities went to great lengths to share their information and use the commission as a vehicle for bringing international attention to the issue.

Fieldnotes from the Great Port Cities of China

The commission arrived in Canton, via Hong Kong, on the 14th of February to begin their investigations in Mainland China. From this southern Chinese starting point the Commission travelled north along the coast covering the great commercial centers of Swatow, Amoy, Shanghai, Chefoo and Tientsin, continuing via train to Peking. [14] It was during their stay in these cities that they encountered the Russian diasporic communities.

The commission's unreleased field observations from Shanghai describe the life conditions of the most destitute refugees, living and working in the international metropole. During their stay, Sundquist and Johnson visited two homes for poor or unemployed “foreign” women. The Foreign Women's Home, funded by private donations from wealthy Europeans living in Shanghai and a "Convalescent" home for poor or unemployed women of the “white Race”, run by the King’s Daughters, a Christian philanthropic organization. [15] Sundquist reported that the homes were populated almost exclusively by Russian women seeking work in the city’s large entertainment industry, working mostly as dancing partners and entertainers in the local cabarets and dancehalls. [16] One report reads:

“Some of the Russian girls are in houses for soldiers, some are streetgirls, many of them soliciting very openly in Broadway and the streets nearby at nighttime. Some Russian girls are mistresses of wealthy Chinese men, the low-class prostitutes take Chinese customers, some even rickshaw coolies at 20 cents.” [17]

Although observed through a lens of racial and classist distaste, these notes allow us an unofficial and more unfiltered gaze at the varied experiences of some of the poorest refugees among this community. We get a sense of the opportunities of employment and sustenance, legally and illegally, and the support network available in the city. Along with these reports, the archival folder contains a note, by stenographer Marshall, on Shanghai’s nightlife and the British soldiers partaking in it. Marshall, being British himself, must have spent a night following in the soldiers' footsteps. He describes how the soldiers would go to one of two cabarets on Thibet Road, not “out of bounds” for them. The Cabarets had Russian, Chinese and Japanese dancers, and the customers were almost exclusively British soldiers. He goes on to describe the existence of a known but unlicensed brothel in Shanghai’s International settlement. The women there were examined by a private doctor, and occasionally by the military police. Marshall concludes: “All the girls in the house are Russian, I was told.” [18]

Newspaper cutout: advertisement for Russian dancing partners for cabaret in Tientsin. Zaria, Harbin, 22.05.31. League of Nations Archives, Geneva.

These unofficial observations, showcase some of the commission's initial encounters with the Russian refugees who had made their way from Manchuria to Shanghai. Looking at the final report, we see how these encounters, within the metropole, led them to discover the patterns and forces driving this movement of people and services. The commission concluded that this was caused by 1) a demand for “occidental prostitution” from large western communities and entertainment industry within these cities [19] 2) a surplus of impoverished and refugee Russians in Manchuria. [20] Taking our cue from this pattern of migration, we now turn our attention to the commission’s journey into Manchuria.

Travelling to the Root of the Matter

On the 13th of May the commission left Peking, venturing into Manchuria, via the regionally significant Chinese Eastern Railway (CER). This elaborate and far-reaching railway network facilitated and guided mass migration, acting as a navigation tool for refugees. With Harbin, its geographical and logistical center, this city naturally became a hub for many of these Russian refugees. [21] The commission stayed in Harbin from the 21st to 28th, working out of their temporary headquarters at the Grand Hotel. They reported that the local Russian community was especially invested in the investigation, enriching it with large amounts of unofficial local accounts. [22] The Harbin files are extraordinary, because they contain a range of testimonies “from below”, capturing perspectives absent from all the other parts of the Asian investigation. [23] They provide verbatim testimonials from the women in question, and a window into the realities of these displaced and destitute communities.

During their investigations in Tientsin, the commission got news of an organized group of traffickers, led by a man named Belousoff, working out of Harbin and facing trial at a local court. [24] This case, and its alleged perpetrators, featured as a continual interest of both the commission and the local community, possibly because of the seriousness of the alleged crimes. The timeline and status of the case is not entirely clear, but the file contains a testimony from a young Russian woman named Alexandra Stephanovich. Through the commission’s interview with Alexandra, and local news coverage of the court case, we have records of Alexandra's testimony translated into English. Alexandra tells a story of deceit, kidnapping and entrapment.

Her story begins with Belousoff offering her a job as a shop assistant in Tientsin under false pretense: “Just before our arrival at Tientsin Belousoff told me that I was not to be a shop assistant but that I would serve in a house of rendezvous. I did not know what that meant.” [25] After being removed from Harbin, and her family, she was forced to work at a brothel in Tientsin. According to her testimony, she was immediately sold to a brothel in Peking after the traffickers got news that Alexandra’s family had found out about her whereabouts. After being escorted back by local Harbin police, years later, she ended up testifying in court. From the reporting on the case, we get Alexandra's concluding remarks “I am ill. I am no person now. I am ashamed to look into people's eyes” brought in the Russian newspaper Zaria and translated by the commission. [26]

The level of coercion and lack of choice makes Alexandra’s story an extreme case. The local press presented her story as an archetypal case of the, at the time, prevalent notion of white slavery. [27] Zooming in on the origins of her personal tragedy, the lack of employment in Harbin, provides us with an understanding of structural effects paving the way for this exploitation.

The additional evidence collected by the commission allows us to grasp a more varied perspective on the circumstantial hardships and lived experiences driving this regional industry. On the 26th of May the commission interviewed a local Russian doctor, named Antonivaya. According to her statement, she examined 74 Russian prostitutes twice a week and had over 20 years’ experience performing police mandated examinations and treatments of licensed prostitutes. [28] She told the commission that most of the women entered the field on their own volition yet pressured by the lack of other options.

“All of them are [working in this capacity] of their own free will at present. They say "Where can we go, we have no place, we do not know how to work, nobody would take us and we could only starve”. They are all in the hands of the keepers because they are all held by a system of debts.” [29]

Antonivaya’s analysis of the dynamics of choice and coercion is corroborated by two other prostitutes interviewed by the commission on the 25th of May at the Grand Hotel. They both entered the brothel on their own accord but were quickly fixed in a system of debt. This seems to be a general modus known by the official authorities. [30] One of the sex workers named Tatiano Dimietriano elaborates.

"The debt is made at the beginning and a girl is never able to pay. Every girl has a debt, some even owe a thousand dollars or more, lately business has been very bad and the girls cannot work the debts off and then we are told there are bills, though what they are for we do not know, but they say the money is owing.” [31]

The stories and testimonies in the Harbin files – these unofficial accounts – impacted the commission’s thinking. The testimonies highlighted circumstantial vulnerabilities driving the markets and allowing for the varying degrees of exploitation. Significantly, the commission saw these larger circumstantial forces and pointed to them as the foundational problem: “It is evident that the root of this evil lies in the precarious economic situation of the Russian refugees”. [32] The problem is thus framed a product of political instability, poverty and displacement experienced by these diasporic communities.

The Commission left the City of Harbin on the 28th of May. What they saw and heard from the local Russian community played a central role in how the case was presented and the urgency given to the matter. They described the environment as a “ready field for traffickers” [33] and called for the international community to rally to the cause and help alleviate the situation of these diaspora communities. This material points to the influential role of the unofficial testimonies “from below”, and how they informed the commissions structural analysis of the causes driving this movement of bodies and services. This branch of their investigation highlighted the aggravating effects of destitution, displacement and insecurity on trafficking in the region.

Concluding Thoughts

The Russian case received an extraordinary amount of attention in the final report’s structure and conclusions. As I have argued elsewhere, this interest was partly down to a form of identification and sympathy projected onto the White Russian refugees, by the researchers, based on notions of race. [34] This could explain why we have the story of Alexandra Stephanovich recorded and kept and not those of her Chinese or Japanese counterparts. [35] Diving into the unofficial accounts and testimonies “from below” we can think along the grain of their data collection and production of knowledge. Such collections of “raw” data allow us to get one step closer to the social fabric, voices and agendas of the communities that the League’s work concerned. Doing this has shown that this unofficial knowledge played a central role in this case. Unearthing the role the Russian community played in the making of this official report, we see how they too used this investigation to set their own agenda and rally support internationally. This allows for a less one-sided understanding of the League’s official reporting and to grasp alternative effects of the League’s global data-collection. A dialogical approach makes way for a decentralized and more richly populated story of human trafficking, that can complement and qualify our analysis of the League’s technical and global campaign to end international trafficking.

Other scholarly accounts focusing on the League’s technical trafficking committees have emphasized the use of legalistic approaches as remedies and understandings of the workers and intermediaries as inherently immoral or psychologically defective. [36] Some work has documented the rise of a more socio-economic discourse throughout the 1930’s. [37] The presentation of the Russian case seems to reflect this development, with an additional eye on larger circumstantial forces of instability, displacement and destitution as the drivers of trafficking. This circumstantial approach, albeit mediated through the gendered, racial and moral thinking of the times, is echoed in the arguments and rhetoric of contemporary analyses of human trafficking. In 2024 the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, released the latest edition of their Global Report on Trafficking in Persons.

“As climate disasters, conflicts, and displacement converge and their consequences cascade, vulnerabilities are growing. Some of the people at the heart of those crises are pushed directly into trafficking and exploitation, others are left without homes and prospects and at huge risk of trafficking, while others still are exposed due to structural risks created by low incomes and insecurity.” [38]

This quote illustrates the continuity in the commission’s framing of the Russian case, and the understandings of trafficking within contemporary international organizations. The commission’s encounter with the destitute and displaced revolutionary refugees, and the conclusions it led them to draw, connects to the volatile and unstable nature of the world today. These forces created, and keep creating, environments, circumstances and structural vulnerability allowing for the exploitation of displaced, poor and disenfranchised people across the globe. Today the ILO estimates that about 28 million people are subjected to various forms of forced labor globally. [39]

References

[1] The Titel is cited from the “Commission of Enquiry into Traffic in Women and Children in the East, report to Council” (League of Nations, 1932). 98.

[2] The use of historic placenames and geographical terminology is based on the source material

[3] Paul Knepper, “International Crime in the 20th Century: The League of Nations Era, 1919-1939” (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). 96.

[4] Knepper, “international Crime in the 20th Century: The League of Nations Era, 1919-1939”. 91-93. Daniel Gorman, “The Emergence of International Society in the 1920’s” (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012). 106-108.

[5] Quincy Cloet, “Truth Seekers or Power Brokers? The League of Nations and its Commissions of Inquiry” (Aberystwyth University: Doctoral Thesis, 2019). 50-51.

[6] Emma Post, “‘Fighting a ghost’: Collecting data and creating knowledge on sex trafficking in the League of Nations between 1921 and 1939.” Tijdschrift voor genderstudies, vol. 24, no. 3/4, 2021. 308.

[7]Sebastian Vang Jensen, “Occidental Sympathies; The League of Nations’ Anti-trafficking Campaign Targeting the Russian Refugee Communities of Interwar China” (Saxo Institute, University of Copenhagen: Unpublished MA. Thesis, 2023), Sebastian Vang Jensen, “‘This Vilest of Trades’: The League of Nations Anti-Trafficking Inquiry of 1927.” Culture and History: Student Research Papers, vol. 7, no. 1.

[8] “Trafficking in Women 1924-1926: The Paul Kinsie Reports for the League of Nations”, Edited by Jean-Michel Chaumont, Magaly Rodríguez García, Paul Servais, United Nations Publications, vol. 1, 2017. 17-18.

[9] Par Kristoffer Cassel, “Grounds of Judgment: Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). 179-80.

[10] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 127.

[11] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 29.

[12] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 97.

[13] League of Nations Archives (LNA), R3047/11B36563/5580, “Report of Mr. von Schmieden on the tour”, 9-10.

[14] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 15.

[15] LNA, COL116/95/4, Shanghai - Section 3 - Supplementary Information, “V.1 Report on King’s Daughters Society by Dr. A. Sundquist”

[16] LNA, COL116/95/4, Shanghai - Section 3 - Supplementary Information, “V.1 Report on King’s Daughters Society by Dr. A. Sundquist”, “V Report on Foreign Women’s Home. By Dr. A. Sundquist”.

[17] LNA, COL116/95/4, Shanghai - Section 3 - Supplementary Information, “V.1 Report on King’s Daughters Society by Dr. A. Sundquist”

[18] LNA, COL116/95/4, Shanghai - Section 3 - Supplementary Information, “Note on British Soldiers in Shanghai, by Mr. C. E. Marshall”

[19] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 35

[20] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 29.

[21] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 30.

[22] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 17.

[23] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 496-512.

[24] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “C. President District Court”. 1-2.

[25] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “L. Testimony of Russian Girl in Case Above”.

[26] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “Extract from Russian paper “Zaria” re above case”. 2.

[27] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “Extract from North China Daily Mail, Tientsin, re White slave traffic”.

[28] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “E. Lady Doctor connected with the Police”. 1.

[29] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “E. Lady Doctor connected with the Police”. 3-4.

[30] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “Reply to Commission’s Questionaire, Handed over by Commissioner of Foreign Affairs”. 3.

[31] LNA, COL118/97/5, Harbin – Questionnaire, “R. Prostitutes and Debts.”. 2.

[32] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 35.

[33] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 36.

[34] Jensen, “Occidental Sympathies; The League of Nations’ Anti-trafficking Campaign Targeting the Russian Refugee Communities of Interwar China”.

[35] LoN, Commission of Enquiry into Traffic. 496-512.

[36] Magaly Rodríguez Garzia. “The League of Nations and the Moral Recruitment of Women.” International Review of Social History, vol. 57, no. S20. 2012. Jessica R. Pliley, “Claims to Protection: The Rise and Fall of Feminist Abolitionism in the League of Nations’ Committee on the Traffic in Women and Children, 1919–1936.” Journal of Women’s History, vol. 22, no. 4, 2010.

[37] Post, “‘Fighting a ghost’: Collecting data and creating knowledge on sex trafficking in the League of Nations between 1921 and 1939.”. 309.

[38] Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report on Trafficking in Person 2024 (United Nations Publications). Preface.

[39] International Labour Organization (ILO), Walk Free, and International Organization for Migration (IOM) “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage” (Geneva, 2022). 2.