“A Feeling of Melancholy Resignation”: The League Visits the Nordic Countries in 1936

Blog post by Emil Eiby Seidenfaden.

In late 1936, a delegation from the League of Nations Secretariat visited the Nordic countries – Finland, Sweden, Norway and Denmark. The delegation met with decision-makers, League proponents and members of the media. In this blog, I dive into the archival traces of this visit, asking one broad question: What do such visits tell us about how League information officials worked in practice – and how does this work complement, nuance or challenge our current understanding of League Information work?

On 9 November 1936, three international officials of the Information Section of the League of Nations Secretariat arrived in the Finnish capital of Helsinki by ferry after having taken the train from Geneva via Basel, Berlin and the Baltic States. Beginning the visit in Helsinki and continuing to Turku and Tampere in Finland, the delegation would travel west and south through the region, to Stockholm and Uppsala in Sweden, then Oslo, Norway and finally Copenhagen and Aarhus in Denmark, spending approximately five days in each country.1

Below, I first present the delegation, its members and its purpose, then discuss their activities and interactions in the four countries, focusing particularly on Denmark, and finally draw out some preliminary conclusions to answer the questions posed above.

The Information Section was one of a dozen Secretariat sections, a large and well-funded section throughout the League’s existence, particularly in the period 1919-1932. Its purpose was to oversee all kinds of publicity and information of the League and its three main bodies – the Secretariat, the Council and the Assembly. It did so in several ways, including offering press services, gathering information for the League, publishing books, pamphlets and other material, and by liaising with League proponents and stakeholders across the world, whether organized in interest-groups or organizations or simply influential individuals. .

The trip to the north was an example of this last-mentioned endeavor. Secretariat documents clearing the journey with its internal financial controllers labeled the journey a “liaison mission” to the four northern states.2 More specifically, the purpose of the mission was to “establish closer contacts with the press and public opinion of the four Northern countries, and to gain some first-hand impressions of their attitudes towards the League.”3

The mission and its members

The three League officials represented three levels in the Secretariat hierarchy, while at the same time bringing individual special skills on the trip. First, Adrianus Pelt, who was Dutch, was the Director of the Information Section and thus led the delegation. Pelt had been Director for two years, having, in a sense, reinvented it, after the Frenchman Pierre Comert and his American second-in-command Arthur Sweetser had, respectively, left the Secretariat and been relocated within it, and the section had been cut to about half its original size.4

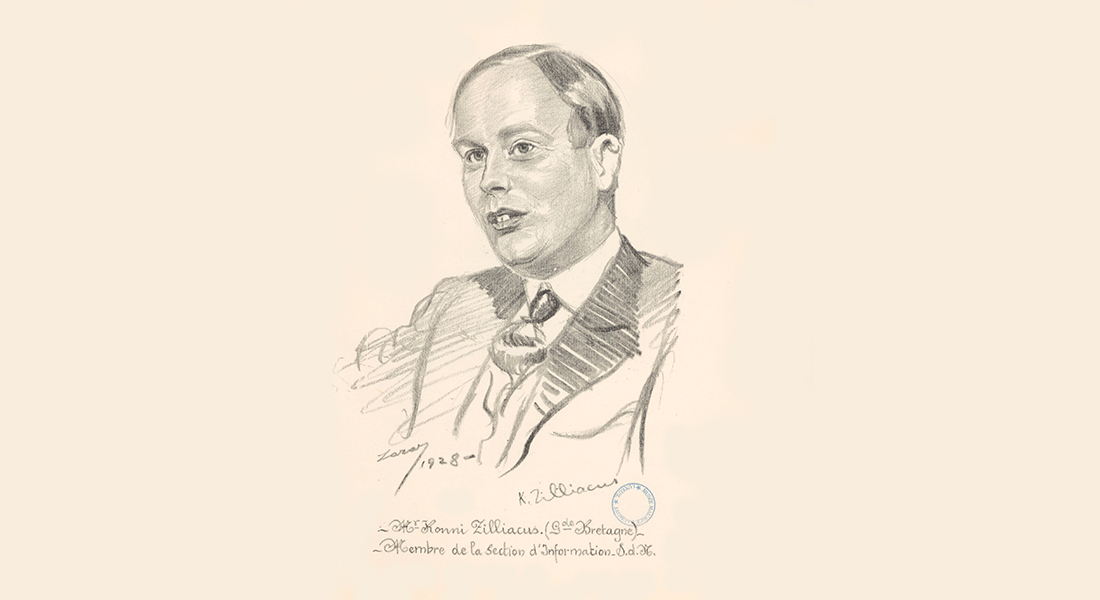

Pelt was known as competent and, according to his former chief, Comert, an “excellent linguist”.5 Konni Zilliacus, a Brit with Finnish roots was a ‘Member of Section’ and thus belonged (like Pelt) to the so-called First Division of Secretariat officials.

Finally, Henriette Rieber-Mohn joined her colleagues as the delegation’s sole female member. She was Norwegian and worked as a Senior Assistant in the section, a Second Division-position. She joined the delegation as assistant to Pelt, but it is evident from the Secretariat Treasury’s documents, that she was to be treated as a Member of Section in her allowance, so that she could travel with the same comfort-level as her colleagues. This likely reflected the fact that her work was highly valued by her superiors. In 1937, her Personnel File contains correspondence between the high officials, in which Pelt argued for her promotion to “a higher rank” and requested, encouraged by Rieber-Mohn herself, that an exemption from an internal examination should be made. Such an exemption, she pointed out, had been made for another Scandinavian official, the Dane Gabriele Rhode.6 Rieber-Mohn’s promotion never happened, probably due to economic constraints, but she used Pelt’s recommendations in her later career during and after the war.7 Pelt himself clearly appreciated Rieber-Mohn as an official, but also wrote in 1938, in a section of her annual evaluation which queried about the official’s ability to work together with others, that she:

“[…] suffers from a kind of inferiority complex which tends to give her the belief that because she is a woman, her merits are not sufficiently appreciated […]”.8

Such a comment, in the context of our project, is highly interesting, pointing as it does to a gendered kind of exasperation with Rieber-Mohn, at the same time as he did not completely disregard her demands as is seen from the fact that he argued, the previous year, for her promotion and praised her overall skills. It is an example of how a broad reading of these personnel files may provide an intimate look into the social dynamics of the Secretariat.

Catching up with collaborators

From the detailed program attached to the mission report we learn that the three officials followed a packed program, meeting with high-ranking civil servants, representatives of industries, “feminine organizations” and student unions. They also made a great effort to meet representatives of the press, meaning editors and proprietors of the most substantial liberal, conservative and labor-based dailies of each country (at a time when a party-aligned press-system was dominant in all four Nordic countries).9 They also met with the ministers for foreign affairs in all four countries, and in Finland they took tea with the country’s First Lady, Alma Svinhufvud.10

Glancing at the mission’s stated purpose one sees that the officials met with these decision makers and opinion-leaders because they saw it as instrumental to understanding ‘public opinion’ in each country. The Information Section was driven by a consistently elitist understanding of the nature of the public, even if they were starting to question the assumption during the 1930s.11 Liaison in general was important – the personal bonding and exchange of information with important people whose enthusiasm for the League’s project made them, in a typical League phrasing, “collaborators” in its legitimization strategies.

In my recently published book on this subject, I argued that the Information Section’s scheme of inviting such people to Geneva as ‘temporary collaborators’ was a cornerstone in its legitimization strategies, and that they expected these people to go home and advocate the League’s cause from within educational institutions, parliaments, in editorial rooms or in national public administrations. The Nordic visit included two prominent examples of how this thinking was applied. On 16 November in Stockholm, and on several following occasions, they had lunch with Otto Johansson, chief of the political section of the Swedish foreign ministry “and previous temporary collaborator of the Information Section”.12 On 18 November in Uppsala, they also met Axel Brusewitz, a professor of political science who had also been Temporary Collaborator (and who would later mentor the influential Swedish liberal thinker Herbert Tingsten).13 Clearly, these people were considered ‘friends of Geneva’ who were now wielding influence and could introduce League officials in formal or informal diplomatic capacities.

The press

The press was a natural main character in the Information Section’s self-narrative and work. Section officials were predominantly former journalists or editors themselves and always made sure to visit colleagues within the press offices of member states’ ministries of foreign affairs and editors of influential papers, often (but not necessarily) moderate, liberal and League friendly ones. From these meetings, they asserted they got a good impression of “public opinion”, not necessarily understood as one, coherent body, but at least as a reflection of popular sentiment within the most important strata of society.

As I have argued elsewhere, the section considered itself a stakeholder in the professionalization and institutionalization of the twentieth century press. With the League’s Conference of Press Experts in 1927 and the section’s participation in the enormous PRESSA conference in Cologne a year later, the League had signaled their devotion to the idea that the press, on top of disseminating news and commentary, carried a responsibility for ‘moral disarmament’: News media should contribute to amiable relations between nations.14 The section, after all, consisted of people who, on top of their journalistic careers, had worked in governmental press offices or even as war propagandists, so the idea of a marriage between journalism and state power in the service of peace was not as alien as a nowadays view of journalism as a ‘fourth estate’ might make it seem.

A thought-provoking perspective is added to this, when we observe the delegation’s visit in Denmark. Here, the delegation met with (among others) Karl I. Eskelund, a prominent journalist at the liberal daily Politiken. Eskelund received the delegation in his capacity as President of the Fédération Internationale des Journalistes – the international association of journalists, founded in 1926.15 Two years after the League-visit, in 1938, Eskelund would be appointed director of an office in the Danish foreign ministry whose prime task it would be to censor the Danish press so as not to provoke German aggression. After Germany did invade Denmark in 1940, Eskelund continued in this role, fundamentally an executor of preemptive self-censorship to avoid direct German coercion of the media.16 After the war, he left journalism, but was appointed ambassador of Denmark to New Zealand, and thus transitioned to a diplomatic career.

The contours of a double-edged character of the League’s understanding of the press emerge. On the one hand, the press was becoming consolidated as the voice of public opinion, a scrutinizer of old diplomacy and therefore an ally of the League. But on the other, it was understood as an institution with a broader societal or ‘moral’ responsibility. Although Eskelund’s 1938-appointment obviously had little to do with what League officials had imagined, this resonates strangely when the moral responsibility became one of keeping the peace in Denmark, even when the country was occupied by a hostile power. The idea of a marriage between the free press and state power suddenly came to mean that the “moral responsibility” was one of protecting the legitimacy of the Danish policy of peaceful collaboration or acquiescence vis-à-vis Nazi Germany.

Back in 1936, the delegation deemed that Denmark was “probably the Northern state which feels itself in greatest danger of invasion”. The officials reported that they had often heard from Danes:

“[…] heartfelt relief that Denmark had ceased to be a member of the Council. There is no hostility but rather a feeling of melancholy resignation that the League has failed and that the world is drifting towards a great war and no way out is visible […]”17

Although the public mood was considered particularly darkened in Denmark, this was indicative of the trip in its entirety. In Norway, although there was less panic, “the desire to keep out of trouble dominates […] conceptions of foreign policy”.18 Sweden, although much better armed than the other Nordic countries, gave an impression of cautiousness and unwillingness to take part in any sanctions against Germany proposed from Geneva. Finland, on edge as well, was equally apprehensive and unconvinced of the League’s capabilities, fearing a Soviet invasion.

Conclusions

The visit by Pelt, Zilliacus and Rieber-Mohn, of the League of Nations Information Section, to the four Nordic countries gives us an opportunity to observe, as a case study, how the Secretariat, during its late period, applied legitimization strategies in practice, and how it gathered intelligence on the League’s standing in -public opinion’. The picture that emerges corresponds to how we understand genuine diplomatic visits today. The most important talks were with foreign secretaries, heads of governmental press offices, leading businesspeople and representatives of interest groups and what we would today call NGOs.

However, to this we can add that the Information Section took great pains to visit representatives of the press (editors, union-representatives and proprietors) covering the left-right political spectrum but excluding the extremes. It seems the Information Section upheld, even after the reductions in its mandate and size in 1933, a semi-diplomatic role. This role in practice meant that the League’s understanding of public opinion fused with what one might call ‘official opinion’, and wider public sentiments become at least as invisible to us, as it must have been to them too.

This points us further to how the visit illuminates the League-understanding of ‘collaboration’ with the public. I argued in my book that this collaboration can be understood as an ever-expanding circular economy or network building to the supposed benefit of the League’s public standing. The Information Section would invite ‘influential people’ to Geneva on internships and label these guests ‘temporary collaborators’, with the explicit purpose that they would then further the League’s cause in their home countries, working from influential or powerful positions in the state, academia, business or media. The Nordic visit included a few examples of the League visiting its former temporary collaborators.

Finally, and with a nod to the ambitions of INNER_LEAGUE, there are indications that the Secretariat hierarchy of three “divisions”, reflecting pay-grade and status, was less important than normal during such a mission, when one must take full advantage of skills and resources. Henriette Rieber-Mohn, despite being female and despite her station in the Second Division, was given a prominent role, travelled freely with her two First Division male companions and co-authored the mission’s report.

- League of Nations Archives (LNA), R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 2, Rapport”, Annexe, 2.

- LNA, R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 1, “Warrant for a Journey on Mission: A. Pelt”.

- LNA, R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Rapport”, 1.

- Emil Eiby Seidenfaden, Informing Interwar Internationalism. The Information Strategies of the League of Nations, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2024), 89-94.

- LNA, S852 (Adrianus Pelt Personnel File), “Pierre Comert: Certificate as to grant of annual increment: Monsieur A. Pelt”, 1 November 1928, 8-10.

- LNA, S867 (Henriette Rieber-Mohn Personnel File), “Career in Secretariat”; More on Gabriele Rhode ,see Karen Gram Skjoldager, “De sendte en dame: Gabriele Rohde i London 1940-45” in Krig, Rom & Cola: Et Festskrift til Nils Arne Sørensen, (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, 2021), 85-102.

- LNA, S867, “Copie d’une lettre de M. Pelt […] à M. Vidnes […]” 9. January 1940.

- LNA, S867, “Second Septennial Report on an Official’s Conduct and Capacity, in Coformity with the Provisions of Article 62 in the Staff Regulations” Mme Rieber Mohn, 17 May 1938.

- League of Nations Archives (LNA), R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 2, Rapport”, Annexe, 2; Svennik Høyer, “The Rise and Fall of the Scandinavian Party Press” in Horst Pöttker, Svennik Høyer, Diffusion of the News Paradigm 1850-2000, (Nordicom: 2005).

- League of Nations Archives (LNA), R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 2, Rapport”, Annexe, 2.

- Emil Eiby Seidenfaden, Informing Interwar Internationalism. The Information Strategies of the League of Nations, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2024).

- League of Nations Archives (LNA), R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 2, Rapport”, Annexe, 3.

- League of Nations Archives (LNA), R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 2, Rapport”, Annexe, 4.

- E. g. Heidi J. S. Tworek, “Peace through Truth? The Press and Moral Disarmament through the League of Nations” Medien & Zeit vol. 25 no. 4, (2010), 16-28

- Emil Eiby Seidenfaden, “Karl Imanuel Nielsen Eskelund” in Kristoffer Schmidt, Jes Fabricius Møller (ed.) Efterslæt – et festskrift til Sebastian Olden-Jørgensen, (Den Danske Historiske Forening, 2024), 83-89.

- Seidenfaden, ”Karl Immanuel Nielsen Eskelund”; Rasmus Kreth, Pilestræde under Pres: De Berlingske Blade 1933-45, (Berlingske Tidende/Gyldendal, 1998).

- League of Nations Archives (LNA), R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 2, Rapport”, 16.

- League of Nations Archives (LNA), R5694, 50, 25243, 1719, “Mission du Directeur et Membres de la Section d’Information au Finlande et dans les pays Scandinavies Nov-Dec 1936”, Jacket 2, Rapport”, 14.